In the hurried world of print journalism, little time goes by between seeing an exhibit and writing about it. But it’s been nearly two weeks since I visited the historically important, uniformly intelligent, and often gratifying show of video art at Brandeis’s Rose Art Museum, and the images in “Balance and Power: Performance and Surveillance in Video Art” remain fresh and provocative. That in itself suggests that the exhibit is more indelible than its initial impression.

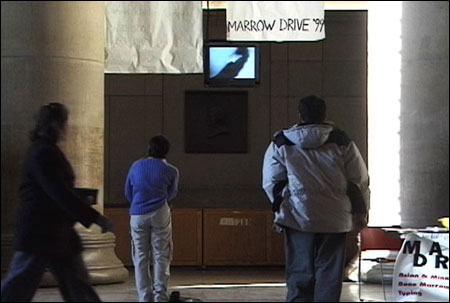

LOBBY I: What’s everyone at MIT looking up at?

|

Michael Rush, the Rose’s new director and this show’s curator, makes the case in an accompanying essay that the emergence of video art in the 1960s corresponded with the government’s use of surveillance equipment, photos, and videos as tools in thwarting anti-war and civil-rights protesters. Aesthetics, entertainment, and social control are indeed twined, but not only because of their proximate birth dates. Artists took it upon themselves to film unsuspecting subjects or to employ surveillance footage as elements of artistic production.

But that doesn’t explain how a good deal of the work included in “Balance and Power” got to be there. Martha Rosler’s filming of herself being measured head to toe (Vital Statistics of a Citizen, Simply Obtained, 1977) may be making a statement, but it’s hardly about Big Brother, since she issued the invitation to the man measuring her, as well as a few female onlookers, and oversaw the procedure. Similarly, the fascinating Political Advertisement VI, 1952–2004 from Antonio Muntadas and Marshall Reese, a string of television ads for American presidential candidates, is a study in slick propaganda techniques, not high-tech surveillance.

The good news is that the exhibit’s lack of categorical unity doesn’t much matter: whether a particular video fits its organizing principle or not, these works mostly stand on their own — as surveillance-inspired documents or seminal artifacts of video art’s beginnings or as genuine artistic accomplishments. Jonas Mekas’s Award Presentation to Andy Warhol gives us the latter two as we become witnesses to what feels like a camp, metaphorical orgy. In the short film, Warhol presides over a good-looking group of Factory regulars (including Baby Jane Holzer and Gerard Malanga). He receives as an “award” an assortment of fruit and then ceremoniously distributes the phallic-shaped food to his cohort. In the silent, somewhat slowed-down black-and-white footage, we watch as the participants feed themselves and each other; they stare with ironic amusement into the camera as if to say, “You know what our chewing symbolizes.” With waifish authority, Warhol moves among them, dispensing his comestible trophies as well as the camera’s fixed attention. You feel you’re part of getting away with something naughty or forbidden, a form of public group sex no one can object to. Surveillance — whether by a government, a gated community, or a peeping Tom — is predicated on its subject’s ignorance of being recorded. Award Presentation is the opposite, a self-conscious if not narcissistic celebration of standing in the spotlight. Which is why it’s fun.

More in keeping with the spirit of surveillance is Tim Hyde’s unassuming Untitled, Bus (2005), which depicts the faces of passengers as they appear in the windows of a city bus they’ve boarded at night. How he did this without his subjects’ written consent I can’t imagine, but his zoom lens allows us to do what we can’t in person on public transportation: stare at the face of someone who has no idea he or she is being watched. It’s like looking into people’s very thought processes as you watch the trajectory of the facial muscles go from greater to lesser tension as they settle into their seats and you begin to feel you know these strangers. The film ends with one young man catching sight of the videographer and staring back at him, the beginnings of annoyance rippling his brow.

LOBBY II: The answer is concealed under Jill Magid’s clothing.

|

The phrase “take a picture” suggests that photography and film share elements of assertiveness and appropriation. We take a picture in the same way we take pride in, take umbrage at, and take our time with: we leave with something. Kiki Seror takes picture taking to a level beyond Hyde. In her Modus Operandi (2005), we see a close-up of a woman applying, in accelerated time, eye liner and mascara. We see the applicators and the eyes of the woman, who through the acceleration of her actions and the enlargement of her features becomes a ghastly emblem of self-absorption verging on mutilation. Despite the vividness with which the footage has lodged in my memory, I’m not convinced of its lasting importance. We experience, à la Warhol, some degree of preening any time we see a live performance. And we experience, à la Hyde, voyeuristic excitement whenever we look at somebody who’s unaware of our presence. We do not similarly experience 24-inch eyelashes repeatedly stroked by 36-inch brushes at the speed of a ceiling fan; exaggerate in size and velocity any mundane, personal action — nail clipping or shaving or applying deodorant — and you’d have something similarly unsettling. A hidden camera in a make-up mirror makes for surveillance, but not necessarily art.