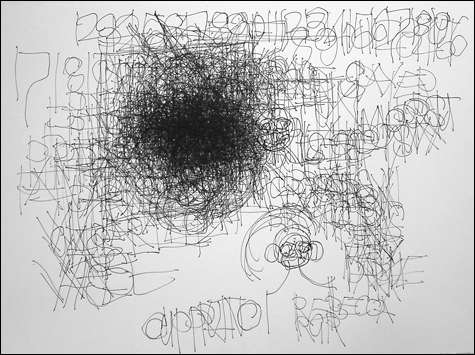

UNTITLED: Dan Miller’s piece is both an expression of and an homage to debilitating compulsion.

|

I’m not sure when the word “salon” started to mean an all-inclusive sampling of a gallery’s artists, but the “summer salon” exhibits that currently dot the city offer the sort of crowded, measured excitement I associate with suitcases packed for summer vacation. Designed to maximize content, they emphasize comfortable, well-worn staples but also admit to a few new items.

That’s true of the exhibit at the Berenberg Gallery: most of the artists on display have enjoyed wall space in the past. Yet it’s hard to say that anything’s “worn” at this space. Lorri Berenberg has carved out a niche in the Boston art world, focusing on — what to call them? — outsider, naive, self-taught artists. Many are handicapped, physically or mentally; few, if any, are schooled; none holds an MFA. And the roiling, vibrant, image-rich, symbol-laden art they produce enjoys a vitality that their studied counterparts on Newbury Street and in the South End would do well to emulate.

Two works in this chock-a-block show stand out, perhaps because they speak in visual whispers whereas the surrounding frames all but shout. Born in 1945 in El Salvador, José Nuñez has been associated with an artists’ collective in San Francisco since 1993. His Seven Figures belongs to a larger series of muted, upright, androgynous, nearly identical figures: they wear white shrouds suggesting a temple frieze, and their rectilinear, side-by-side, unpunctuated forms suggest a row of neatly packed sardines. Do not, repeat, do not look at this work on the gallery’s Web site; what in real life is soft to the point of vaporous — they could be votive candles seen through a fog — becomes unduly bright and articulate. The magic of Nuñez’s acrylic-and-magic-marker painting lies partly in its homespun majesty; the figures are both caryatids and cartoons. And they appear to bear witness; square-shouldered and facing forward, they become a Greek chorus, an army battalion, a living fence.

On the far edges of Dan Miller’s 2005 untitled black ink drawing, large numerals, thin as a hornet’s legs, rise up out of the chaos of dark lines that occupy the middle of the picture. Below them, brief apparitions of the alphabet quickly dissolve into an indiscernible (but not undifferentiated) overlay of needle-like marks. What’s remarkable about the piece beyond its strange compositional integrity — it’s like a large piece of sooty lace frayed on its entire circumference — is the utter certainty it conveys about the marks you can’t make out. There’s no possibility that the dark tangle of squiggles is anything other than repeated sequences of numbers and letters; were it a wire sculpture and not a drawing, each of the interwoven figures could be lifted out with a pair of tweezers. Why that matters and how that gives the work its near magnetic power, I’m not sure, except that there’s no hint of self-consciousness or gimmickry. The piece is both an expression of and an homage to debilitating compulsion.

FIVE FIGURES: You have to see José Nuñez’s homespun majesty in person.

|

Neeta Madahar’s first body of work — though I wasn’t sure what to make of it initially, I’ve come to appreciate its incandescent power — was diabolically simple: she photographed birds at her backyard feeder with the searing flash of a strobe light. The effect was comical and eerie, the quotidian made surreal by the artist’s having figured out that she could both capture and transform the commonplace: the events and characters were normal, blue jays and chickadees on a manufactured perch, but the colors were so rich, the light was so bright, and the animals were caught in such a nanosecond of surprise, that the effect was unsettling, unworldly.

The Madahar body of work on display at Howard Yezerski Gallery continues the tradition of blurring the line between natural and unnatural, though the feel is now more cerebral, less arresting, perhaps ultimately more pointed. This time she’s taken a slew of handmade origami flowers and arranged them directly onto the photo paper. By manipulating the light, she makes the images of more or less identical arrangements read quite differently. Some are as varied and colorful as a jar of mixed jellybeans; others, on black backgrounds, become luminous, underwater jewels. Another set of photograms has had the color eliminated altogether; the resulting pattern of blossoms resembles delicately scalloped charcoal.

The organizing principle behind these experiments with light and form is evident when you take in the whole show, but I wonder how a single one will read on its own. The playful inquisitiveness that is apparent as you move around the various groupings is sure to be attenuated or disappear entirely when a solitary photo finds its way into a home or a museum or onto another wall. What began as an iconoclastic send-up of the natural world is threatened with looking, well, normal.