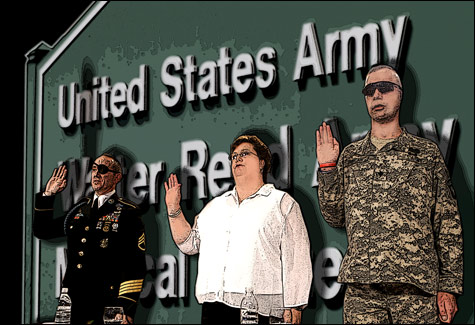

GRIEF AND GRIEVANCES: Wounded soldiers and their families testified in front of a US House subcommittee last week to the squalid conditions at Walter Reed, the army’s top medical facility. |

When next year’s Pulitzer finalists are announced, the Washington Post’s coverage of dismal conditions at Walter Reed Army Medical Center will almost certainly make the list. The February 18 and 19 stories by Dana Priest and Anne Hull were exemplary pieces of journalism: beautifully written and packed with grisly detail, they showed that the same troops lionized for their role in the “War on Terror” are neglected by the government after they come home. And they shamed the highest levels of government into quick action. After the Post’s pieces ran, President George W. Bush allegedly told White House spokesman Tony Snow, “Find out what the problem is and fix it”; since then, three top Army officials have resigned or been fired.

Considering the Post’s reputation, its influence in Washington, and Priest’s renown, neither the quality nor the impact of the paper’s Walter Reed coverage was surprising. But did the Post actually break the story? On February 20, Joan Walsh — editor-in-chief of the online magazine Salon — reminded readers that Salon’s Mark Benjamin had written about Walter Reed in 2005 and 2006, focusing on the poor care received by soldiers with post-traumatic stress disorder and traumatic brain injuries. While Salon’s stories didn’t quite match the sweep and narrative power of the Post’s, the underlying message was the same: Walter Reed, Benjamin found, “is failing to properly care for many soldiers traumatized by the Iraq war.” Walsh’s tone was gentle, but she did note that one military couple whose ordeal Benjamin had described — Corporal Wendell McLeod Jr. and his wife, Annette McLeod — were prominently featured in the Post’s coverage, including a front-page, above-the-fold photograph on February 19.

In subsequent days, Editor & Publisher, National Public Radio’s On the Media, and New York Times columnist Paul Krugman all highlighted Salon’s previous work on the Walter Reed story. But not the Post. On March 1, Priest was asked in an online chat why the Post’s stories had received more attention than Salon’s; she replied that she hadn’t read Benjamin’s reportage. That same day, the Post ran an article by Hull and Priest headlined HOSPITAL OFFICIALS KNEW OF NEGLECT: COMPLAINTS ABOUT WALTER REED WERE VOICED FOR YEARS. Salon wasn’t mentioned.

In an e-mail to the Phoenix, Post ombudsman Deborah Howell said Benjamin had done “fine work,” but added that Hull and Priest were pointed to the story by a tipster; that Hull only read one of Benjamin’s stories before she and Priest wrote theirs; and that the Post’s material was original and only overlapped slightly with Salon’s. Also, Howell said, Hull didn’t know Benjamin had mentioned the McLeods until after the Post’s story ran. “It’s not uncommon (it has happened to me) that work done by large news organizations brings about more acknowledgement,” she concluded.

Parallel universes

Being a journalist means not having to admit someone else got there first. Unlike academics, reporters can largely ignore their predecessors’ contributions to a given story — naming an occasional colleague or competitor if we’re feeling generous, dropping in “reportedly” now and again, or maybe just giving no credit at all. This probably improves readability, especially in lengthier, more complex stories. It also lets journalists deceive the public — and themselves — with a flattering illusion of self-reliance.

If blithe appropriation is a professional luxury, being the object of appropriation is less pleasant, even when the stakes are much lower. In June 2005, I reported in the Phoenix that pizza-magnate-turned-Catholic-crusader Tom Monaghan planned to bar pornography, birth control, and abortions from Ave Maria, his new town in Florida. Eight months later, the Associated Press relayed this information without attribution; Monaghan then embarked on a PR offensive that featured appearances on Today and Good Morning America. I should have been pleased the story was growing; instead, I was annoyed I wasn’t getting any recognition.

Given this pettiness — which I hope isn’t wholly unrepresentative — it’s no surprise that some journalistic veterans see the debate over whether and how to credit as relatively insignificant. That’s the view of Bob Phelps, who was the Times’ Washington editor from 1965 to 1974 and then ran the Globe’s coverage of the busing crisis. During his time in the capital, Phelps recalls, the Times’ New York editors regularly urged the DC bureau to acknowledge competitors’ scoops — and the DC bureau regularly resisted. “We said, ‘Well, that subject was on our list, and we just didn’t happen to choose that particular day [to cover it],” says Phelps. If a story demands coverage and can’t be significantly advanced, he adds, whatever competitor broke it should definitely get a nod. Still, “Outside of the newspaper industry, or the media in general, who cares whether you give credit or not?”