THE SILENCE: Joseph Beuys stacked reels from Ingmar Bergman’s 1963 film and galvanized them in silver so that they can never be projected.

|

George Maciunas was the sort of artist who composed musical scores that called for hammering nails into all the keys of a piano. He organized concerts at his New York gallery in 1961 that developed into festivals when he moved to Germany the following year. At one, his Korean-born pal Nam June Paik performed another pal’s “score” — “Draw a straight line and follow it” — by dipping his head in a bowl of ink and dragging his hair along a long sheet of paper on the floor. At another, the German sculptor Joseph Beuys wound up a pair of toy-clown drummers and set them atop a piano to play.

Maciunas dubbed his very loosely organized movement Fluxus — as in “flux,” or flowing and changing. The goal was a “nonprofessional, nonparasitic, nonelite” art in which anything could be art and anyone could make it. He declared in a 1965 manifesto: “This substitute art-amusement must be simple, amusing, concerned with insignificances, have no commodity or institutional value.”

“Multiple Strategies: Beuys, Maciunas, Fluxus” at Harvard’s Busch-Reisinger Museum, however, insists on the institutional value of the output of this gang of philosophical jokers. Curatorial assistant Jacob Proctor has assembled a two-room exhibit of dozens of “multiples” — artworks manufactured in large editions — from Harvard collections. It’s great, smart, funny stuff. Just be prepared for lots of reading.

The Fluxists, who hailed from the United States, France, Japan, Germany, and Korea, were an obscure, heterogeneous group united by Maciunas, some shared impulses, and the fact that they didn’t much fit in anywhere else. Fluxus was a descendant of dadaism, a movement of primarily European artists who responded to the mechanized slaughter of the First World War with satiric nonsense and absurd art because, in their eyes, reason and propriety had gotten them into the war. Of particular influence was Marcel Duchamp, who sailed to New York to avoid the fighting and freaked people out when he redefined what art could be by producing “readymades,” mass-produced objects like shovels, bottle racks and — notoriously, humorously — urinals transformed into art because he said so. A later inspiration was American musician John Cage’s chance compositions and “readymade” music. His three-movement 1951 score 4’33” called for the “performer” — David Tudor at the premiere and frequently therefore — to sit at a piano and play nothing for four minutes and 33 seconds. The “music” was just the ambient noise in the room.

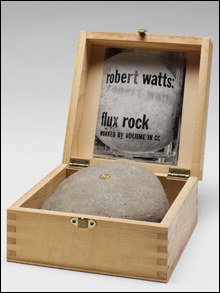

Fluxus works often adopt the form of absurd scores or lovely haiku-like instructions. George Brecht’s Water Yam (circa 1964) is a box of printed cards saying stuff like “Piano Piece . . . A vase of flowers on(to) a piano” and “Two Vehicle Events — Start/Stop.” The cards of Mieko (Chieko) Shiomi’s Events and Games (circa 1965) read, “Music for Two Players II — In a closed room pass two hours in silence (They may do anything but speak)” and “Disappearing Music for Your Face — Smile/Stop to smile.” Robert Watts’s Events (circa 1965) offers this: “Mailbox Event — open mailbox/close eyes/remove letter of choice/tear up letter/open eyes” and “Winter Event — snow.” The goal is not perfect execution but a democratic, anyone-can-do-it style that opens the work up to anyone willing to try it or even think it.

FLUX ROCK MARKED BY VOLUME IN CC: Robert Watts’s piece is open to anyone willing to try it — or even think it.

|

Fluxus artists aimed to make art cheap, remove it from galleries, cut down pretension, so they created small gags, puzzles, and toys; these were often sold out of the Fluxshop that Maciunas opened in New York in 1964. The packages, unified by Maciunas’s bold, clear designs and type, played straight man to punch lines inside. Maciunas’s Burglary Fluxkit (mid 1960s) is a box filled with random keys. Yoko Ono’s A Box of Smile (1971) is a box with a mirror in the bottom. Jock Reynolds’s Fluxsport: Great Race (late 1960s) presents four tiny snail shells lined up on the left side of a little box, as if at a starting line. Ken Friedman’s A Flux Corsage (circa 1969) is a box containing a packet of flower seeds.

Maciunas assembled crates of small works by numerous Fluxus artists. Flux Medicine are capsules filled with nothing but air. Ben Vautier’s wicked anti-establishment joke Total Art Matchbox is a box of matches labeled “Use these matchs to destroy all art — museums art library’s — ready-mades pop-art and as I Ben signed everything work of art — burn — anything — keep last match for this match [box].”

The Fluxus works wear Harvard’s institutional embrace lightly, but it’s a cosmic, ironic joke that all these anti-institutional art toys are quarantined in museum vitrines, never to be played. Somebody should sell cheap facsimiles.