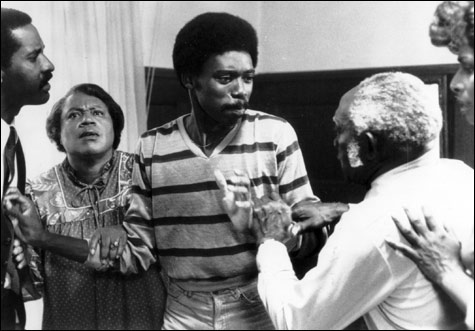

MY BROTHER’S WEDDING: Another story of hope and defeat among the denizens of South Central LA.

|

Lyrical, contemplative, with a clear disdain for mainstream Hollywood, the African-American filmmaker Charles Burnett — the subject of a 10-day series at the Museum of Fine Arts beginning June 8 — has cobbled out an unorthodox career, mostly on the sidelines of American commercial film. He was trained in the ’70s at UCLA. While Hollywood was churning out blaxploitation features, Burnett was struggling to develop an alternative approach to African-American subjects: a mixture of urban naturalism (most of his movies were filmed in South Central LA) and visual poetry rooted in the images of great Depression-era photographers like Walker Evans and Dorothea Lange. His plaintive, haunting, one-of-a-kind feature

KILLER OF SHEEP

(1977; June 8 at 8:15 pm; June 9 at noon; June 10 at 4 pm; June 14 at 4:20 pm; June 15 at 6:20 pm; June 16 at 12:30 pm; June 17 at 12:15 pm) is often held up as an example of what independent film artists can achieve, but very few people have actually seen it, and in the three decades since he made it, the trajectory of his work has been hard to trace. Occasionally his name pops up on a television drama or a documentary, and he’s made two movies intended for general release: To Sleep with Anger (1990), a family drama starring Danny Glover, and The Glass Shield (1994), which focused on racism in the LAPD. But To Sleep with Anger, an attempt to find a distinctively African-American cinematic narrative form based on fable, is mostly baffling, and the conventional story line of The Glass Shield is such a terrible fit for Burnett’s gifts that you can’t even make sense of the plot.

Killer of Sheep, restored, is the centerpiece of the MFA series, which also includes “THREE SHORT FILMS BY CHARLES BURNETT” (“Several Friends,” “The Horse,” and “When It Rains”: June 9 at 10:30 am; June 10 at 2:30 pm),

MY BROTHER’S WEDDING

(1983; June 14 at 6 pm; June 16 at 2 pm), and Billy Woodberry’s

BLESS THEIR LITTLE HEARTS

(1984; June 16 at 4:15 pm; June 17 at 10:30 pm), for which Burnett supplied the script and took charge of the cinematography. In the rambling, episodic “Several Friends,” which he made in 1969, you can see the genesis of Killer of Sheep — glimpses of life, stalled and frustrated but sometimes comic and often sensuous, lived with inadequate resources against a dilapidated cityscape. In the most eloquent (and funniest) scene, a young husband gets a friend to help him move a washing machine, but they can’t squeeze it into the space where it’s supposed to go, and when another friend appears to pick them up for a party in Hollywood, he gets exasperated because they haven’t even showered, and finally he decides it’s too late to hit the party. (It’s Waiting for Godot for young black men stuck in South Central.) And in My Brother’s Wedding, you can see Burnett reworking the landscape of Killer of Sheep to carve out another story of hope and defeat among the denizens of this LA ghetto — the protagonist, Pierce (Everett Silas), is a directionless young man, still living off his parents at 30 and working in his mother’s cleaning shop — but with only intermittent success.

Burnett works so far out on his own wavelength that you can’t predict when one of his movies, or even one of his sequences, is going to come together. He tries to capture the natural conversational rhythms of his subjects, but in “Several Friends” the combination of untrained actors and poor sound recording sometimes makes those rhythms more lulling than vivifying. And in My Brother’s Wedding, some of the actors (especially Gaye Shannon-Burnett, in the unenviable role of the bourgeois black woman engaged to Pierce’s socially mobile brother — a character Burnett obviously detests) are awkward in an entirely different way: they come across as self-conscious amateurs. My Brother’s Wedding moves between odd, elocution-class scenes — like a disastrous family dinner at the bride’s parents’ home — and loose, shambling scenes built around scruffy characters Burnett is more comfortable with. (In one, an old woman comments to her grandson that her hair has blue dye in it because her hairdresser does whatever she wants “and I don’t have nothin’ to say about it.”) But in Killer of Sheep, a minor-key rhapsody on the life of a slaughterhouse worker named Stan (played by the terrific actor Henry Gayle Sanders, who has a wonderful, open face with deep-set dark eyes), every detail feels magically right, and the acting is simple but amazingly expressive. And in the 13-minute “When It Rains” (1995), where a community-minded man wanders the neighborhood to scare up enough money to prevent a local landlord from evicting a woman and her daughter on New Year’s Day, the humor and charm emerge effortlessly from the compact dramatic situation.