SHAMAN: The rogue was inextricable from the teacher, the quackery essential to the cosmology. |

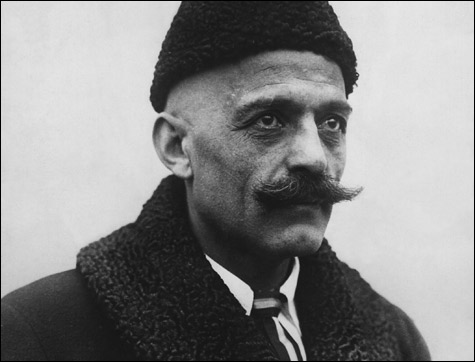

The Arlington Hotel, Cambridge: March 6, 1924. His disciples must have shown him the newspapers, and we may imagine the guru perusing them over his morning coffee and cigarette, and then — through his haze of breakfast benignity — starting to rumble with colossally interiorized laughter. “GURDJIEFF RITES AMAZE BOSTON,” ran the front page of the Boston Post. “Wonderful Dances of Asia Set Before Audience of ‘Intellectuals’ Cause Thrills in Plenty.” Breathless description followed of an evening of ritual movements and telepathic demonstrations at the Fine Arts Theatre that was attended by the cream of the local professoriat and presided over by a wizardly figure with “shining shaved head, piercing eyes and upturned mustachios.” The story immediately above it on the Post’s front page, an unrelated account of a crooked horse-race tipster, was headlined “MASTER ROGUE IS AT IT AGAIN.”

Was Georges Ivanovitch Gurdjieff a charlatan? Plenty of people thought so, then as now. Edmund Wilson scorned him supremely; D.H. Lawrence thought him the perpetrator of “a sickly stunt.” To Frank Lloyd Wright, on the other hand, he was “the greatest man in the world.” And the writer Katherine Mansfield, who was dying of tuberculosis, delivered herself almost blissfully into his care. (Others since who have at one time or another claimed the influence of Gurdjieff’s work and writings include Alan Watts, Timothy Leary, Keith Jarrett, and Robert Fripp.) A minute in Gurdjieff’s presence sufficed to convince one that he had mastered something: the man reeked like garlic of strange powers and supernatural attainments. But the rogue in his personality was so inextricable from the teacher, the quackery so essential to the cosmology, that even his most devoted acolytes were kept in a sort of refined agony of doubt as to the nature of his intentions.

Gurdjieff, who died in 1949, was of Greek-Armenian descent and arcane provenance: his date of birth is unknown, he claimed to have spent his early years gathering knowledge in the caves and monasteries of the East, and he bore the scars of at least two bullet wounds on his body. His English was broken and rich in profanity. His system — the Fourth Way, or “The Work” — offered a comprehensive program for the breaking down and reassembly of the “human machine.” At his Institute for the Harmonious Development of Man, at Fontainebleau, in France, where aristocrats toiled in the scullery and intellectuals were sentenced to dig holes till their hands bled, he would from time to time shout “STOP!”, obliging everyone within earshot to freeze, mid action — the soil, as it were, still spilling from their lifted shovels. Arriving in Manhattan in January 1924 on the liner SS Paris, accompanied by 30 of his followers, Gurdjieff saluted the waiting photographers with an ironic tip of his astrakhan hat. “Comes To Save America,” ran the caption in the New York Times, equally ironic.