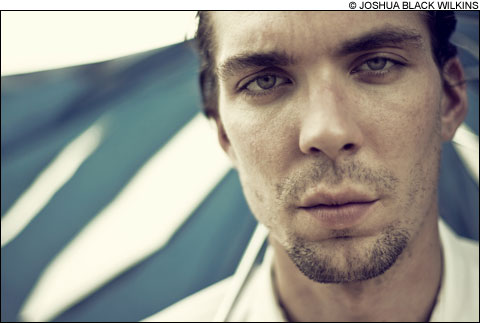

ROUGH HOUSING: “I have a long history of issues with drugs and alcohol,” says Earle, “and they rear their ugly head up sometimes.” |

No one wants to stand in the shadow of his famous family. But will Justin Townes Earle's recent arrest for disorderly conduct make people forget that he's the son of country-music vigilante Steve Earle? Or will it remind them of his father — whose own past substance-abuse problems are well storied.

The 28-year-old Tennessee native is now back on the road after jail time and voluntary rehab following an incident on September 16 at Radio Radio in Indianapolis that took in — if you believe the disparate accounts — a pay dispute, a drunken brawl, damaged property, egomaniacal ravings, and a great show (or was it a pitiful performance?) by Earle and his band. Earle's only comment is that the accounts are inaccurate — and the most inaccurate part, for him, would surely be any suggestion that the concert sucked. Just two days earlier, he had released his fourth album in as many years, Harlem River Blues (Bloodshot), an accomplishment overtaken by what ultimately amounts to a less interesting story. Anyone standing too far away shouldn't judge him by the sins of his father. After all, this is rock and roll.

"I started off a lot like Paul Westerberg, chewing on a microphone and screaming his face off," says Earle (who comes to Royale on Friday), when he recalls his lack of ambition in his early days. Westerberg would seem to be a carefully chosen patron punk saint, a modest figure in the canon of the great ones in blue jeans and simple dresses — Woody Guthrie nodding beatifically from the nave, "Mother" Maybelle Carter just behind the altar, Brother Springsteen fixing the organ before the Sunday morning service. It would be a lie to say that Earle doesn't sit in these pews thinking about his own starry-eyed destiny. (And having a middle name like "Townes" doesn't hurt.) But for Earle's church, the divorce of real religion from the traditional music that he lives and breathes was a necessary one. "The problem with religious music is that every song I've ever heard about God . . . is the same. It just leaves you with less to work with."

Keeping the microphone out of his mouth is not a problem now. Earle croons with the kind of sophisticated ease that's usually reserved to describe naturals like Lyle Lovett. Hearing it from the man himself, you would think that any pedigree he does possess has more to do with his coordinates than with his DNA. "When Springsteen decided to do what he did, it was a lot harder for him. He was from the Jersey shore. The music that he was really into — Roy Orbison and the early rock and roll that he loved, it was an import. But I'm from the buckle of the Bible Belt, which is where all of that stuff started, began, and where it's from."