Contemporary Indian literature has been making a home in the United States for a while now thanks to Salman Rushdie, Vikram Seth, and Arundhati Roy, among others. There are the more recent arrivals too: Jhumpa Lahiri, Kiran Desai, and Kaavya Viswanathan, a Harvard freshman who earlier this year landed a two-book deal from Little, Brown for an advance projected to be in the mid six figures.

Contemporary Indian literature has been making a home in the United States for a while now thanks to Salman Rushdie, Vikram Seth, and Arundhati Roy, among others. There are the more recent arrivals too: Jhumpa Lahiri, Kiran Desai, and Kaavya Viswanathan, a Harvard freshman who earlier this year landed a two-book deal from Little, Brown for an advance projected to be in the mid six figures.

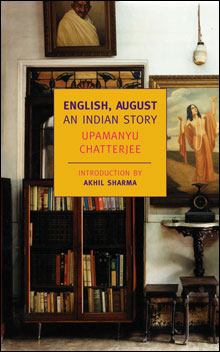

Originally published in 1988, and now making its American debut, in paperback, Upamanyu Chatterjee’s English, August: An Indian Story was a bestseller in India. This first novel can be shelved with the work of his compatriots if need be, but a few delightful differences set it apart, the first and most obvious being its protagonist. Agastya Sen is a 24-year-old slacker whose primary activities are masturbating, smoking pot, and contemplating his place in the larger order of things.

When we first meet Agastya — or August, or English, or Ogu, as he’s sometimes called — he’s getting high with his friend Dhrubo on the eve of his departure for Madna, the dusty, remote city where he’ll spend his first year of training in the Indian Administrative Service (IAS). As Akhil Sharma writes in his introduction, belonging to the IAS is a bit like being a movie star in India; approximately two million people compete for fewer than 100 entry-level positions. Agastya, however, is met with skepticism when he reveals his IAS status to a fellow traveler on the train to Madna. He doesn’t look the part of a clean-shaven bureaucrat, and he has his own self-doubts. As he sits in his first meeting with fellow officers, “he was again assailed by a sense of the unreal. I don’t look like a bureaucrat, what am I doing here. I should have been a photographer, or a maker of ad films, something like that, shallow and urban.”

Agastya characterizes himself as a megalopolitan Indian, “who ate hamburgers and knew who Artoo Detoo was.” Unlike the uneasily acclimatized expatriates of Jhumpa Lahiri’s fiction, he’s remained in his home country. Yet he experiences the same feelings of rootless confusion. His mother died when he was young; his father is a distant government official who communicates primarily through formally written letters. When Agastya cites Beckett’s Waiting for Godot, his uncle expresses irritation: “Why is it . . . that the first thing you are reminded of by something that happens around you, is something obscure and foreign, totally unrelated to the life and languages around you?” Agastya can’t even find solace in music: “his own taste had no continuities — merely a sad mongrel hybridity,” he realizes. His nicknames, August and English, reflect his affinity for all things Anglo.

Nowhere is this sense of disconnect made more palpable than in Madna, the backwater that Chatterjee evokes with precise lyricism and humor. Removed from the distractions of Delhi, Agastya can avoid the deadening reality of his bureaucratic post only by getting stoned, reading Marcus Aurelius on the nature of man’s fate, and engaging in hilariously tedious social engagements at the behest of his boss.

Nowhere is this sense of disconnect made more palpable than in Madna, the backwater that Chatterjee evokes with precise lyricism and humor. Removed from the distractions of Delhi, Agastya can avoid the deadening reality of his bureaucratic post only by getting stoned, reading Marcus Aurelius on the nature of man’s fate, and engaging in hilariously tedious social engagements at the behest of his boss.