DECIPHERED “This is not a Dan Brown novel.” |

Last Saturday morning, a small crowd gathered inside the entrance to Brown University's John Carter Brown Library. The group — a mix of Brown and RISD undergrads, professors, and curious locals — was soon ushered across creaking floors, past tapestries and manuscripts, and down a flight of stairs to a basement conference room. There waited Lucas Mason-Brown, a Brown senior from Belmont, Massachusetts with a double major in math and the philosophy of science. A PowerPoint slide with the headline "Roger Williams Mystery Book" glowed on a screen at the front of the room.

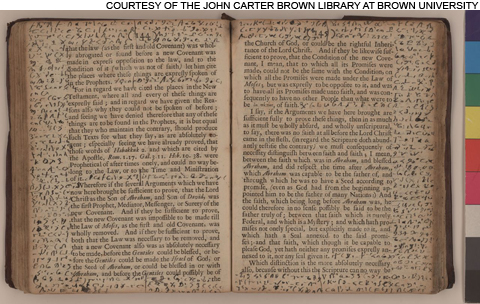

"I'd like to talk to you today about some of the work I've done over the past year or so involving a 17th century cipher scrawled in the margins of this book right here," Mason-Brown said. He gestured toward a faded, leatherbound volume perched on a nearby bookrest. The Brown family has owned the book — subtitled "An Essay Towards the Reconciling of Differences Among Christians," full title and author unknown — since the early 1800s, he explained. And though the encrypted scribblings that fill its margins have long been attributed Rhode Island's founder, Roger Williams, scholars have never been able to definitively determine what those notes say.

"About 10 months ago," the student calmly continued, "with the help of a variety of faculty and staff collaborators, I cracked this code and I have since translated nearly 200 pages of encoded material revealing, among other things, an original, never-before-seen theological treatise." A few minutes later — after distributing a key to Williams's encoded alphabet, leading guests through its system of dots, dashes, and crude pictograms, and explaining his method of pinpointing the text to the last four years of the Williams's life, between 1679 and 1683 — Mason-Brown said, "this is not a Dan Brown novel." The code was likely devised not to thwart other readers, but to save time and paper, Mason-Brown said.

The lecture was part of the Charles H. Watts II History and Culture of the Book Program, a series of public events at the library that range from a seminar about Abe Lincoln biographies to a "rare book petting zoo," wherein students are encouraged to leaf through aged books from Mexico.

The first and last sections of Williams's notes focus on cosmography and medicine. But Mason-Brown's talk focused on the red meat of his discovery: the section of Williams's notes between pages 164 and 207 that plunges into a debate on one of the era's most controversial issues: the baptism of infants and Native Americans. Williams, a champion of religious self-determination fond of stating "Christenings make not Christians," was opposed to both practices.

As Mason-Brown spoke, he flashed onscreen the covers of infant baptism treatises from 1676 and 1679 by theologians John Norcot and John Eliot. Then he switched slides to show an excerpt from his Williams translation that read, "But the words of the Great King our Lord enjoin us to protect the gospel, whose written word [refutes] John Eliot . . . and whose word must prevail over the book of John Eliot. I hope a beam of light will appear to you by my labor." The excerpt — like most of the presentation — was received with a chorus of Huh!'s and Hmphs!'s and awestruck chuckles.