MAIDSTONE: Mailer plays a filmmaker — the heir to Buñuel, Antonioni, and Dreyer — who’s looking to run for president even as he casts a movie that may or may not be pornographic. |

Maybe the trauma of another intractable war has sparked the movies’ recent interest in ’60s headliners: the Beatles in Across the Universe, Dylan in I’m Not There, Vietnam everywhere. This flashback wouldn’t be complete without a look back at the film œuvre of Norman Mailer. If nothing else, a Mailer retrospective provides a window, however distorted and monomaniacal, to a time when writers could be cultural icons as well-known as Paris Hilton is today, a time when movies were analyzed with a passion now reserved for fantasy football. In the ’60s, Norman Mailer was not only a writer, he was a cultural icon. And he aspired to make art movies.

Hence the value of the Harvard Film Archive’s weekend retrospective, “The Cinematic Life of Norman Mailer.” As engaging or entertaining cinema, these celluloid shaggy dogs have their limitations, but then so do the Andy Warhol home movies that were in part their inspiration. Instead, Mailer’s films illustrate the author’s overall theory of film, as described in the section “Film” in his 2003 essay collection, The Spooky Art. The title of the book refers to the art of writing, but it might apply more accurately to film — which, in Mailer’s opinion, is the opposite of writing. Although writing “gets you closer to your soul,” its detachment and the specifying nature of language constricts film’s spontaneity and vital ambiguity. At its best, film can almost re-create external reality itself. At the same time, its power is internal, incantatory, and magical; it is “the physiology of the psyche.” To achieve these ends, it must be improvised, loosely structured, and, it would seem, dominated by an ego like that of Norman Mailer. In short, the ideal auteur combines Warhol’s voyeurism and Kenneth Anger’s shamanism with double shots of bourbon and macho role playing.

Mailer’s first foray into this spooky art fulfilled those ideals, and it did not bode well. After performances of his stage version of The Deer Park in 1968, Mailer and a couple of cronies would drink at a bar and pretend they were mobsters. This is great stuff, they thought, let’s make a movie! So they hired D.A. Pennebaker for $1000, rented a room in a warehouse, filled it with booze and weapons, and let fly.

Or at least Mailer let fly. In WILD 90 (1968; September 23 at 7 pm), he kicks crates, barks at a dog, screams, bellows, sweats, and acts like the belligerent drunk at a party whom everyone tries to placate or avoid. Typecasting, perhaps. The dialogue, what little is audible (Mailer on the film’s sound: “Like it was filtered through a jockstrap”), is scatological, unfunny, and repetitive, like David Mamet on a bad night. Regardless, the film possesses that uncanny quality Mailer valued, the preservation of the past. Even in a home movie, he writes in The Spooky Art, “there is a sense of Time trying to express itself.” He adds that “the years have added magic to what was once moronic.”

Indeed. The same ghostly presence of time recaptured haunts Dick Fontaine’s documentary WILL THE REAL NORMAN MAILER PLEASE STAND UP? (1968; September 22 at 7 pm, with the director present). Maybe the film should have been titled “Will the Real Norman Mailer Please Sit Down?” — especially in the sequence in which a drunken Mailer commandeers the mic at a rally the night before the March on Washington in 1968 and pretty much repeats his performance from Wild 90.

The next day, sober and in a three-piece suit, Mailer joins the half-million demonstrators marching on the Pentagon, crosses a line of MPs, and gets himself arrested. Later that year he would win a Pulitzer Prize and a National Book Award for his “non-fiction” novel about the event, The Armies of the Night. Between the book, perhaps his masterpiece, and Fontaine’s raw footage lies Mailer’s real genius, and it’s not improvisatory filmmaking.

TOUGH GUYS DON’T DANCE: Ryan O’Neal and Isabella Rossellini in a must-see movie that violates every one of Mailer’s previous cinematic principles. |

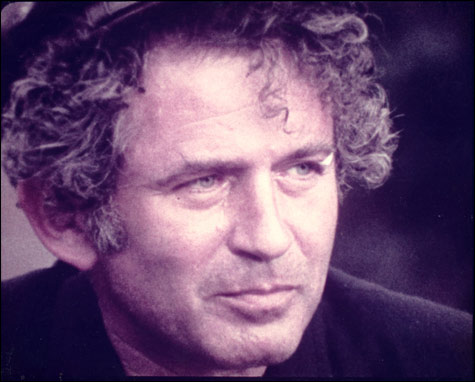

Nonetheless, he was indefatigable. For his next film, he realized he needed a more fertile premise and, perhaps, less of his own ego. In BEYOND THE LAW (1968; September 23 at 8:45 pm), Mailer plays Francis Xavier Pope, a poetic Irish detective (though his accent also suggests a Southern sheriff, or Broderick Crawford in Highway Patrol) enduring a busy night in a New York precinct station. Interrogations of rapists, murderers, and hookers (played mostly by Mailer’s own friends) interweave and evoke at times the electric immediacy of a Frederick Wiseman documentary. Some of the segments come alive with astonishing performances, such as Mailer’s friend Edward Bonetti as a wife killer and an insouciant, brutal Rip Torn as a biker. Even Mailer shines. At the end, he seems to have kissed the Blarney Stone as, with surreal hilarity and a bibulous brogue, Francis confronts his wife (Beverly Bentley, Mailer’s then-wife) with her infidelity.Had Mailer pursued this line of filmmaking, setting up defined but flexible premises, employing cinéma-vérité techniques and explosive, confrontational improvisation, he might have rivaled John Cassavetes. But who wants the tragedy of the everyday when the Apocalypse beckons? And so we have MAIDSTONE (1970; September 21 at 7:30 pm), a film that in its megalomania, perversity, and purity embodies, for better and worse, all the excesses and virtues of the decade then just ended.