The Minutemen and the LA they endured

By JAMES PARKER | June 24, 2006

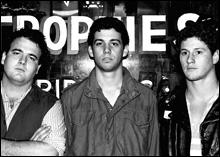

DARK KICKS: In natural opposition to the prevailing culture of bikinis and the Eagles, Hollywood’s punks built themselves a catacomb of violence, addiction, occultism, and Manson-infatuation. |

The Minutemen — and shouldn’t we love them for this? — are getting steadily less graspable, less comprehensible. Back in the ’80s, it seemed fairly straightforward: three LA avant-punkers with a Wire fixation and manic chops smoking through tiny, spiny, jazz-mathematical rock songs at an approximate rate of 45 per hour. Like the other heroic trios of the era — Meat Puppets and Hüsker Dü — they were on SST, and that label’s maximal/minimal æsthetic seemed to apply in more or less the same proportions: the most energy, the least money, the highest ambitions riding in the shittiest van. If you half-closed your eyes, you could almost take them for granted.But contemplating the band down the tube of 20 years, in the new DVD version of Tim Irwin’s 2005 documentary We Jam Econo: The Story of The Minutemen (Plexifilm), we find that they’ve been telescoped into their true rarity and specialness. Even though they were all “bros,” locals, graduates of the same high school in San Pedro, California, the coming together of D Boon, Mike Watt, and George Hurley could have been ordained only by the flukiest gods of chance: this was a one-off if ever there was one. Boon and Watt were shocked from a stupor of ’70s innocence — trance-like repetitions of “Smoke on the Water” played in their bedrooms on out-of-tune guitars — by the early Hollywood punk bands; they roped in Hurley, smiling and surfer-strong, and the radical cell/comedy troupe was complete.

D Boon, huge and taut with his own mass, would prance across the stage, airy, unembarrassable, as if the only thing tethering him to earth were the chord plugged into his amp. Over his bass, Watt churned and blew, and Hurley didn’t so much play his drums as taste them, drawing flavor from every surface. Punk rock had jetpacked them into a synæsthetic sound world where ideas had the same value as chords, where Reagan’s policy in Central America could be related directly to the setting of your amp. “He had the worst shoes!” chuckles someone in Irwin’s film of D Boon, who apparently would not be parted from a pair of ghastly gray loafers because they allied him with the common man. And from Nels Cline we learn that the separation of treble and bass in the Minutemen sound, the gulf between the brilliant scrape of D Boon’s guitar and the bubbling underthrust of Watt-ness, was “a political decision,” an attempt to establish “sovereign states” of noise. Can you imagine, say, Fall Out Boy thinking along these lines?

Related

Related:

Boston in Austin, Remembering Randy Hien, Post-punk pantheon, More

- Boston in Austin

There were 26 bands from Massachusetts in Austin last week to play the South by Southwest music conference Black Helicopter, "Buick Electra" (mp3)

- Remembering Randy Hien

In an unfathomably cruel twist of fate, longtime Living Room owner Randy Hien was killed in a car accident on Monday, September 25.

- Post-punk pantheon

They were, by definition, misfits.

- Low rent

With good singing, acting, and conducting, a stage director for La bohème can afford to keep out of the way, which is pretty much what Ocel does.

- The hottest and brightest

The New England Conservatory is bringing to Symphony Hall the hottest of young conductors.

- Mining the past

John Coltrane acid blasts rage through the Mars Volta’s new The Bedlam in Goliath.

- K-OS

In American hip-hop, nice guys don’t just finish last — they’re lucky to leave the starting gate.

- The 40 greatest concerts in Boston history: 33

Lollapalooza 1995 | Tweeter Center | July 25, 1995

- Opera, opera, opera

Every performance at Santa Fe was packed, and few subscribers left unhappy.

- More than Mozart

One of the spring’s most exciting prospects is the premiere of John Harbison’s But Mary Stood: Sacred Symphonies for Chorus and Instruments.

- Classical giants

Audiences love the Beethoven Seventh. And this audience went bananas. But I didn’t.

- Less

Topics

Topics:

Music Features

, Entertainment, Music, Meat Puppets, More  , Entertainment, Music, Meat Puppets, Pop and Rock Music, Punk Rock, Ian MacKaye, Henry Rollins, Sandinista National Liberation Front, Fall Out Boy, Husker Du, Less

, Entertainment, Music, Meat Puppets, Pop and Rock Music, Punk Rock, Ian MacKaye, Henry Rollins, Sandinista National Liberation Front, Fall Out Boy, Husker Du, Less